Many Americans know that access to health care and the social safety net is restricted for undocumented immigrants but are unaware that it is also restricted for legal immigrants and their families. In 1996, welfare reform created the five-year bar to restrict legal immigrants’ access to safety-net programs. With few exceptions, the five-year bar requires legal immigrants to have a qualifying status for five years before they can receive benefits, even if they are otherwise eligible. While the five-year bar is race-neutral on its face, it was motivated by racist rhetoric and policy analysis that accused Hispanic immigrants of taking advantage of public benefits and even committing fraud. In practice, it disproportionately harms Hispanic families, who are much more likely to be low-income immigrants than any other group.

The five-year bar harms Hispanic immigrant families by denying needed benefits, lowering benefit levels, and increasing administrative burden. This institutional racism denies children in immigrant families, most of whom are U.S. citizens and Hispanic, the full benefit of the safety net. Eliminating the five-year bar would go a long way toward equitably reducing U.S. child poverty for Hispanic children in immigrant families.

Welfare reform restricted legal immigrants’ access to the safety net

Prior to welfare reform, legal immigrants were essentially treated as U.S. citizens in terms of eligibility for the safety net. Welfare reform created two ways to restrict legal immigrants’ access to the safety net: qualified status and the five-year bar.

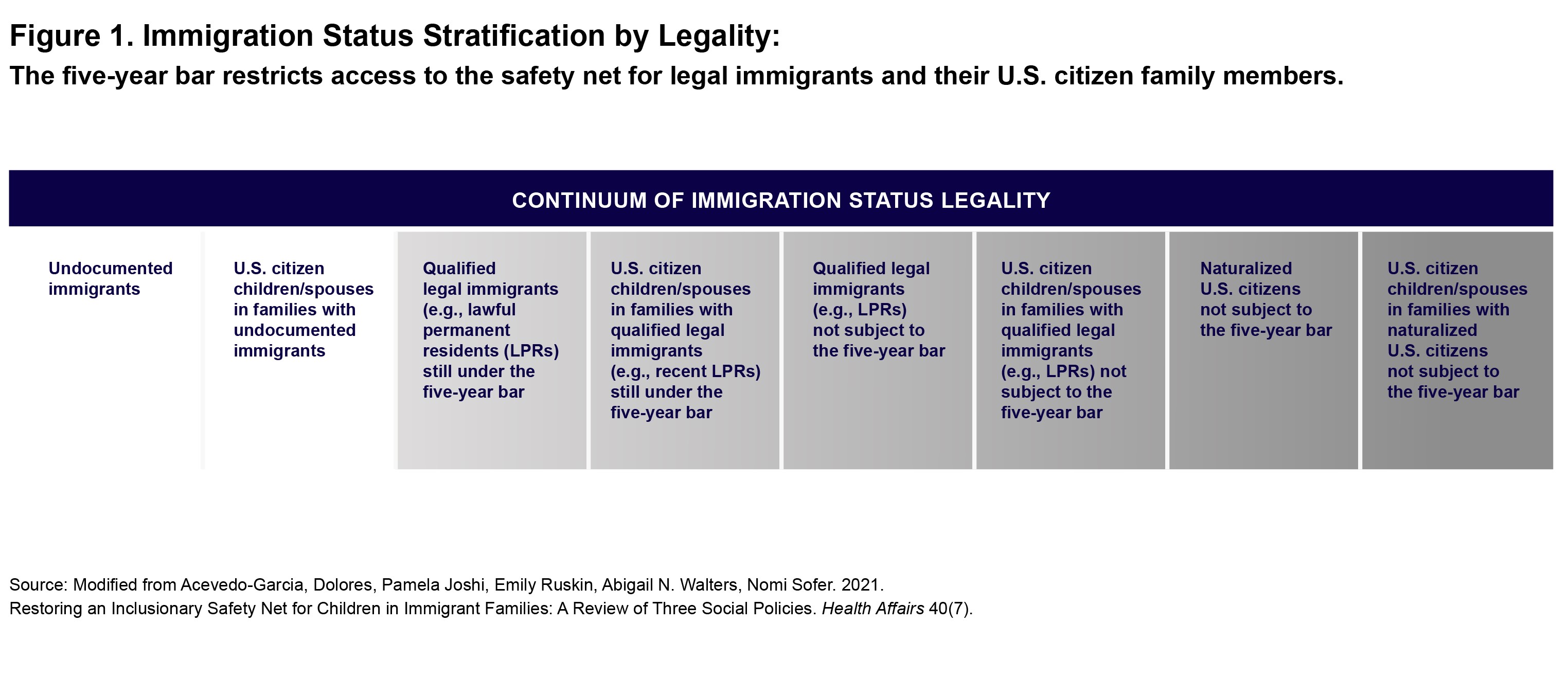

Noncitizens are divided into “qualified” and “nonqualified” categories. And the five-year bar further stratifies immigrants along a continuum of legality that includes legal immigrants, naturalized citizens, and even U.S. citizen children and spouses who live in mixed-status families (see Figure 1). The five-year bar links children’s access to the safety net to the treatment of their families in social policy. Thus, children in immigrant families are denied the full benefit of the safety net because their well-being is conditioned on the status of their parents. This includes parents who are legal immigrants but are subject to the five-year bar.

The five-year bar harms children in immigrant families

Approximately 3.5 million children in poverty (36%) live in mixed-status immigrant families, and because of the five-year bar, many of these children are deprived of important benefits. For instance, citizen children with legal immigrant parents still under the five-year bar cannot receive subsidized child care funded by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, even if they are otherwise eligible. The five-year bar is also combined with other eligibility restrictions to reduce SNAP benefits for children in immigrant families.

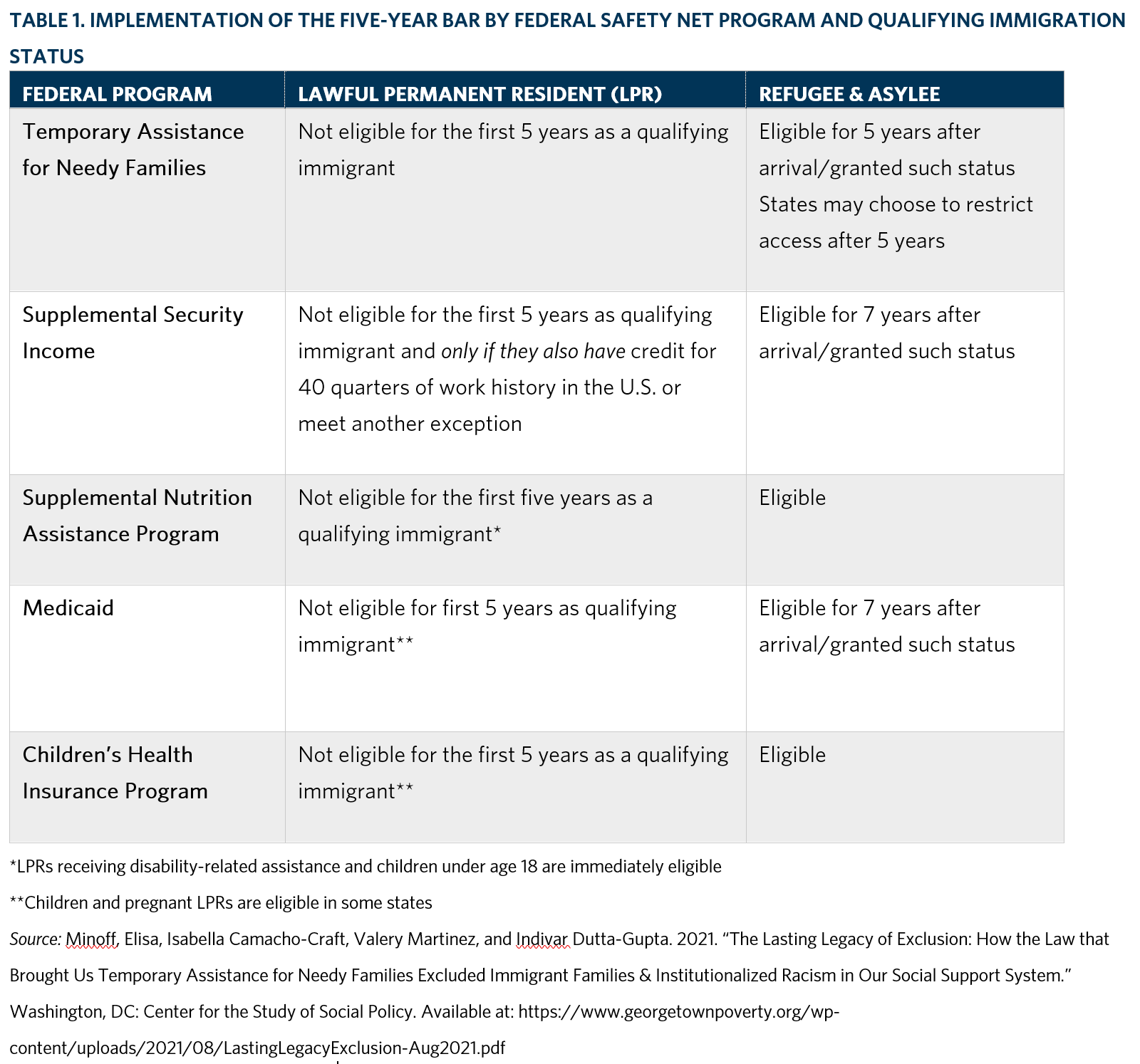

Administrative burden is another harmful consequence of the five-year bar. As shown in Table 1, the five-year bar is implemented differently depending on the federal program and the applicants’ immigration status. This implementation creates overly complex and fragmented immigrant eligibility rules that not only directly deny many legal immigrants needed benefits, but also create excess administrative burden for immigrant families. Administrative burden is the complex and time-consuming bureaucratic procedures that limit access to benefits. To apply for and continue to receive benefits, immigrant families must overcome administrative burdens like learning whether family members have met the five-year bar or one of its exemptions; completing burdensome paperwork to prove length of qualifying status; and managing the stress and fear that applying for benefits could expose the family to immigration enforcement.

Individually and together, each of these consequences of the five-year bar deny children in immigrant families, most of whom are U.S. citizens and Hispanic, the poverty-reducing effects of the safety net.

To equitably reduce poverty, eliminate the five-year bar

The five-year bar was designed and implemented based on the racist belief that Hispanic families were immigrating to the U.S. only to access public benefits, although research has shown that access to public benefits is not a factor in migration decisions. Hispanic children in immigrant families are poor not only because their parents disproportionately work in low-wage essential occupations but also because the five-year bar and other restrictions that target immigrants deny them access to the safety net. Eliminating the five-year bar is a critical step towards “building back better” and equitably reducing child poverty for all children, regardless of race, ethnicity or their families’ immigration status.

More about the exclusion of children in immigrant families from the U.S. safety net