The need to take time away from work to manage a serious illness, care for a loved one or welcome a new child is universal—and the ability do so with job protection is essential to promote equitable employment. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) entitles some employees to up to 12 weeks of protected, unpaid leave in these circumstances, but it is not accessible to all workers. Black, Hispanic and immigrant workers are disproportionately less likely to be able to use it.

To mark the 29th anniversary of FMLA, we’re sharing three policy actions that could eliminate or reduce inequities in this policy.

Inequities in access by race, ethnicity and nativity

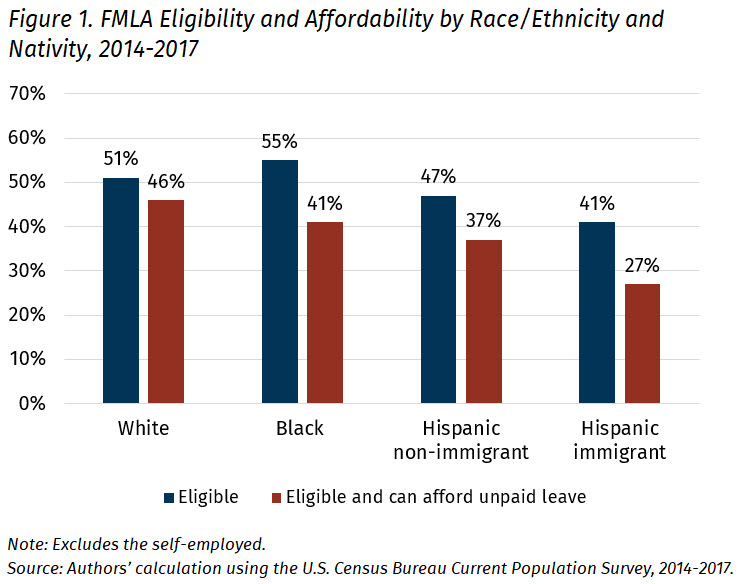

Equity in accessing family and medical leave is shaped by two main factors: eligibility and affordability. Employees are legally entitled to leave if they are employed by an elementary or secondary school, a public sector agency or a private employer with at least 50 employees. Figure 1 presents the eligibility and affordability of FMLA by race/ethnicity and nativity. A higher proportion of Black workers are eligible for FMLA due to their high employment rates in the public sector, and a lower proportion of Hispanic workers, particularly Hispanic immigrant workers, are ineligible because they tend to work for smaller firms.

Because leave is unpaid, affordability—the financial ability to take time off without income—can be a barrier that prevents workers from taking leave, even when they are eligible. When we account for family income, we see that a lower proportion of Black and Hispanic workers are both eligible and potentially able to afford taking unpaid leave.

Action 1: Decrease the firm size requirement

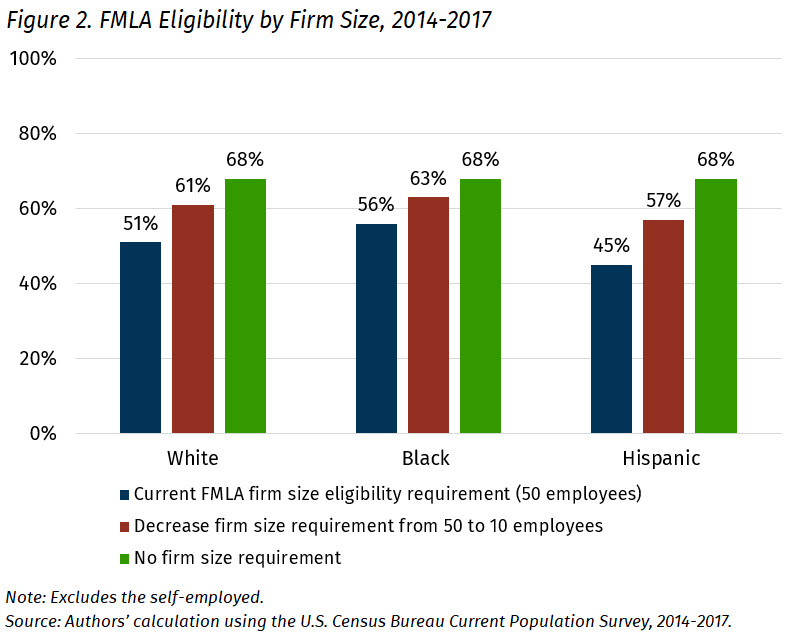

Hispanic workers have lower access to family and medical leave because they disproportionately work for small businesses that do not meet the size eligibility criteria. Figure 2 shows that if the firm size requirement were to be removed, equitable access by race/ethnicity would increase. For example, if the firm size requirement decreased from 50 employees (blue bar) to 10 employees (red bar), access to FMLA would improve the most for Hispanic workers. If the firm size requirement were to be entirely removed (green bar), we estimate that there would be no racial/ethnic difference in FMLA eligibility: 68% of workers across racial/ethnic groups would be eligible.

Action 2: Make leave paid

Making family and medical leave paid would greatly benefit Black and Hispanic working families, who are more likely to live in single-earner households and to have less wealth to stay afloat amid a precipitous drop in wages. If the federal government created a paid leave program—similar to the one in California—we estimate that the share of workers experiencing economic hardship from six weeks of leave during a three-month period would decrease from 18% under unpaid leave to 6% under paid leave. Black and Hispanic workers would experience even larger gains. Paid leave helps prevents economic hardship for all working families, but Black and Hispanic working families are especially vulnerable because their incomes tend to be much closer to the poverty line than White working families. An even more equitable family and medical leave policy would target higher wage replacement for working families with less of a financial cushion.

Action 3: Improve enforcement and outreach

The FMLA is a labor standard, rather than a program. Enforcement is overseen by the U.S. Department of Labor, and it is largely implemented by employers. This implementation can be hampered by employer errors, a lack of employee knowledge and a cumbersome application process, which disproportionately burden black, Hispanic, immigrant and low-income workers. Furthermore, FMLA enforcement has historically been reactive and reliant on employee complaints, a process which may inequitably disadvantage low-wage workers who do not have complete information about their FMLA benefits. Strategic enforcement that is focused on equity implications, such as targeted investigations in low-wage industries that disproportionately employ Black, Hispanic and immigrant workers, or increased funding for monitoring staff, could potentially increase employer compliance and decrease employee burden.

A more equitable FMLA

To a certain extent, our current family and medical leave policy promotes equity by providing unpaid job-protected leave, which is significant because most employers do not provide any paid or unpaid leave. However, FMLA benefits are not universal. The policy excludes almost half of all workers—and many of those who are eligible cannot afford to take unpaid leave. Decreasing the firm size requirement, ensuring leave is paid and improving enforcement and outreach could make family and medical leave more equitable.

Read more about unequal access to FMLA by race/ethnicity